By Tom Goldsmith | Part of our Special Series: Always Canada. Never 51. | This post first appeared in Orbit Policy's Deep Dives

Happy Wednesday, everyone. Today, I want to expand on one thing I mentioned in Monday’s post—Canadian corporate profits and their implications for innovation.

Long story short, the financialization of Canada’s economy and the high levels of rent extraction that accompany it are barriers to innovation. We are impoverishing ourselves over the long term to support short-term financial gains. If we care about innovation and productivity, then we need to focus far more critical attention on corporate Canada.

Let’s dig in.

High Profitability

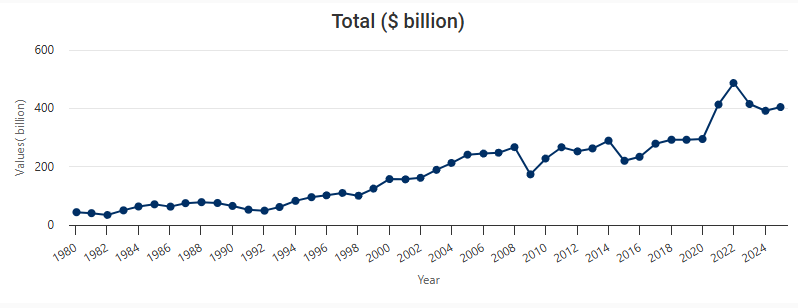

Canadian businesses are immensely profitable. In raw terms, their profits were at near record highs, over $400 billion last year.

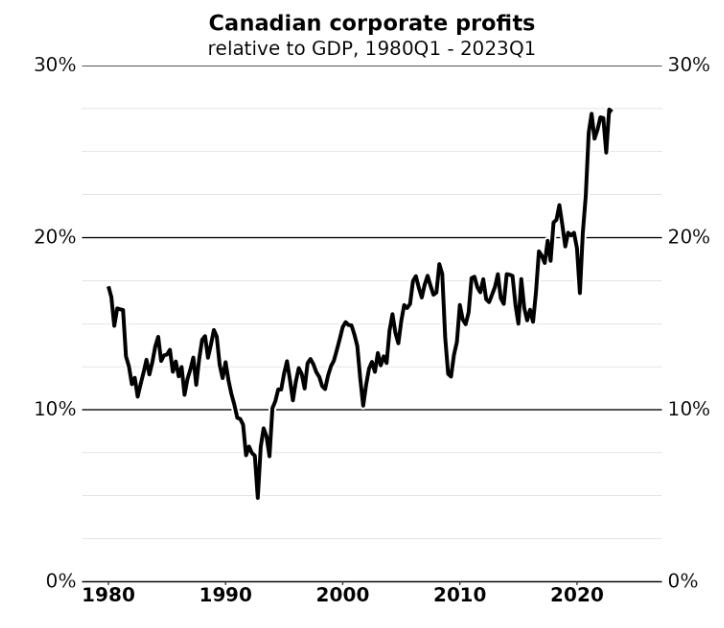

Those profits are also at record levels relative to GDP:

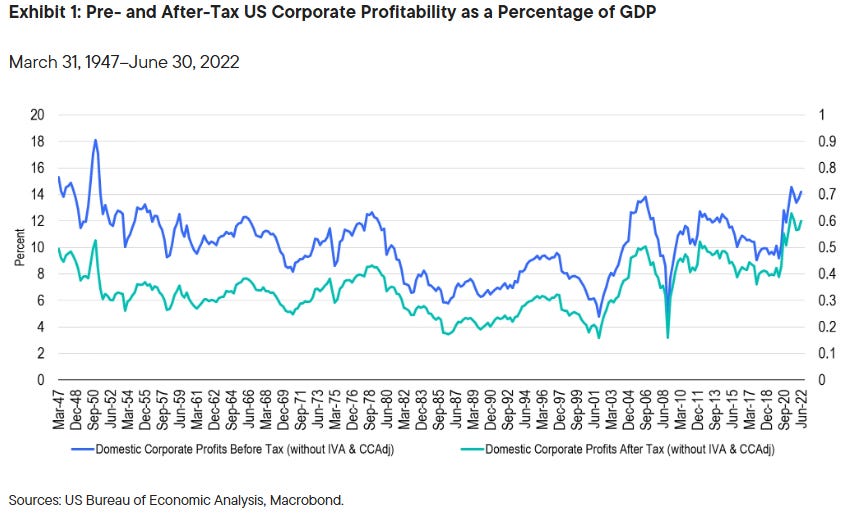

These profit levels surpass those found in the US and have for a long time. If we look at US corporate profitability relative to GDP, we can see that at almost no point over the past 45 years have US corporate profits exceeded the share of GDP of Canadian firms.

Various factors influence these high levels of Canadian corporate profitability, with Peter Josty highlighting a lack of competition, growing company size, and cross-border trade as contributing factors. But what matters most is what is done with those profits, and here the picture isn’t pretty.

Low Investment

Despite profits reaching astronomical figures, businesses simply haven’t been reinvesting them. Business investment on multiple fronts is paltry and a driving cause of our productivity challenges.

Capital investment per worker has been falling. Research from C.D. Howe highlights that in 2024, Canadian workers will likely receive only 66 cents of new capital for every dollar received by their counterparts in the OECD as a whole and 55 cents for every dollar received by their US counterparts. Canadian corporations spend more on structures than the US, but we massively lag in machinery, equipment, and IP products.

Investment in workers lags our peers. Research from Shift Insights for the Future Skills Centre estimated, using the limited data available, that Canadian firms invest only an estimated $240 per employee annually and lag their international peers in rates and hours of instruction.

Investment in R&D is falling. If you are a reader of this newsletter, you probably don’t need this pointed out, but nevertheless, Canada’s business expenditure on R&D has fallen over the past 25 years, and even after a relative improvement since 2017, it remained at 1.07% of GDP in 2023. The OECD average, meanwhile, has been consistently increasing over that time, to a record high of 1.99% of GDP.

Record corporate subsidies. All of this is happening at a time when there are record subsidies to businesses. As Laurent Carbonneau highlighted in his recent book At the Trough, since 2019-20, Canadians have been giving away more than 50 cents of every dollar collected in corporate income taxes right back to businesses. Corporate subsidies are expected to reach $50 billion annually by 2027-28 – the equivalent of $1246 for each person in Canada – and that is before the Liberal platform included a range of new corporate tax breaks.

So, where are the profits going?

In short, to shareholders. Calculations by DT Cochrane found that from 1985 to 2014 around equal shares of profits were distributed to shareholders as was invested in physical assets less depreciation (38% vs 36%). Since then, though, shareholder distribution has shot up, and investments have crashed. From 2020 to 2022, almost 50% of profits were distributed to owners while less than 10% was invested. And as we’ve seen above, there hasn’t been a corresponding jump in investment in non-physical assets such as IP.

But wait, it gets worse

High profitability at a time of paltry investment is bad enough. But there is a further trend that exacerbates the picture—growing rates of dividend recapitalization. As Rachel Wasserman has highlighted, instead of dividends returning profits to shareholders, dividend recapitalization is sourced by taking on new debt. The private equity industry drives this trend, using cash flow, not just profits, to enrich itself.

Companies that take this path have “less cash available for productive activities such as business operations and capital investments. With less cash available, a company may be forced to slash expenses, lay off employees or declare bankruptcy when faced with unexpected hardship.”

Combined, these two trends point to the massive financialization of the economy, which prioritizes short-term rent extraction at the expense of long-term productivity and growth. It is another example of what Alex Usher has described in a different context as us “eating the future”.

Innovators vs Corporate Canada

Where does this leave innovators in Canada? Well, if you care about innovation, pushing forward our knowledge frontier, solving real-world challenges, and boosting our productivity and growth, then I think you need to be clear that you stand in opposition to much of corporate Canada.

There are deep ties between corporate Canada and the innovation economy, not least the links between private equity and venture capital. However, we should see how corporate Canada is a barrier to innovation and not an enabler.

Government procurement is often cited as a way to accelerate innovation in Canada, and it is certainly an important and underutilized lever. But let’s put it into context: The public sector’s contribution to GDP last year was $475 billion. That’s only around 21% of our total GDP of $2.265 trillion. Increasing business investment to the levels of our peer countries would unlock huge innovation and procurement opportunities.

And that is all without analyzing the role of capital accumulation and corporate elites in closing off political routes to innovation. If innovation is a process of creative destruction, we can’t ignore that part of what is being destroyed is the existing elites’ economic and political power. It is no surprise that elites typically oppose genuine innovation.

If innovators support and perpetrate our existing system of rent extraction and financialization, then we will condemn Canada to continuing low innovation and ongoing corporate capture.

We need to rein in corporate Canada. As Lenore Palladino said in the essay I cited on Friday: “The corporation’s privileges come from the public, and we have the right to promote innovation and productivity rather than extraction.”

It is time we realized how far extraction and innovation stand in opposition to each other. Opposing extraction must be an essential part of unleashing innovation.

–

Orbit Policy’s Deep Dives explore how innovation and technology can help build a more inclusive and prosperous society and economy in Canada.

Share with a friend

Related reading

Elbows up: A practical program for Canadian sovereignty | Report

Canada can’t become a sovereign country by doing the same old things, explains a new compendium of essays co-sponsored by the CCPA, the Centre for Future Work and several national civil society organizations. Elbows Up: A Practical Program for Canadian Sovereignty is a response to corporate rallying cries responding to Donald Trump with a familiar playbook: deregulation, austerity, tax cuts and fossil fuel expansion. The collection includes contributions from 20 progressive economists and policy experts, including SCP CEO Matthew Mendelsohn and others who participated in the Elbows Up Economic Summit held in September 2025 in Ottawa.

Pipelines and algorithms aren’t going to save us | The Hill Times

Smart investments in natural resources and AI alone will not get us through this moment of geopolitical rupture. As Matthew Mendelsohn writes in an op-ed for The Hill Times, SMEs contribute just over half of Canada’s GDP and employ 64 per cent of our people. We have to make more low-cost capital available to the smaller businesses, locally owned enterprises, not-for-profits and social enterprises who crucially employ and reinvest locally, act as important local economic infrastructure and provide services that are crucial for well-being. They are automatic stabilizers in the face of tariff threats outside our control.

What’s wrong with mainstream economics?

Mainstream, or “neoclassical,” economics still dominates how we teach, study and understand our economy, even though much of it doesn’t match reality. In this piece, economists Louis-Philippe Rochon and Guillaume Vallet explain why outdated economic ideas persist and how they can lead to harmful policies. They challenge five common myths about inflation, growth and inequality, showing that today’s economy is driven more by power and institutions than by perfect markets. As "heterodox" economists, they argue it's time for a new kind of economics that reflects how the real world actually works.