By Matthew Mendelsohn and Dan Skilleter | Read the research report

Over the last couple of years, there have been dozens, if not hundreds, of articles warning of Canada’s poor economic performance. The mic drop has increasingly been Canada’s poor performance on “GDP per capita.” Canada’s low ranking compared to our peers on growth in GDP per capita has been used to draw a variety of sweeping, negative conclusions about Canada’s economy.

One lobby group is now even using GDP per capita as the only summary measure on which they will evaluate Prime Minister Carney’s progress against key commitments.

But GDP per capita is a deeply flawed measurement for evaluating rich countries and is easily influenced by a variety of factors having little to do with economic performance or economic well-being.

GDP per capita looks at the output in the economy and divides it by the number of people in the country. Many of those writing about the economy have interpreted our poor performance to conclude that our economic growth has been particularly bad.

But compared to other rich countries, Canada’s economic growth has actually been relatively average. So, why has Canada been something of an outlier in this one measurement of GDP per capita growth? The culprit has been the denominator in the equation—population growth—driven by significant increases in temporary residents.

Between 2019 and 2024, non-permanent residents (NPRs) as a percentage of the population increased from 3.6% to 7.4%. These temporary foreign workers and international students contribute comparatively less to our economic output than Canadians.

In new research we released today, economist and SCP Fellow Gillian Petit estimates what Canada’s GDP per capita would have been over the past decade if Canada had kept our temporary resident numbers stable. She also estimates the expected impact on GDP per capita in the coming years due strictly to planned reductions in our intake of temporary residents as outlined in the immigration levels plan.

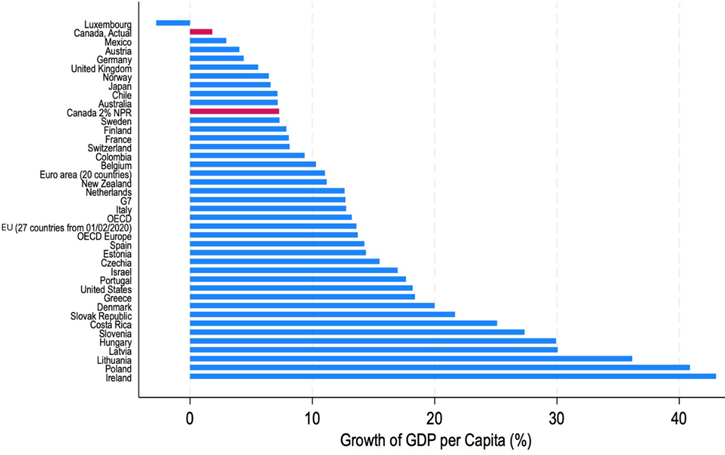

She concludes that if we had maintained our temporary resident numbers at about 500,000—or two per cent of the population—in recent years, Canada’s GDP per capita would look much more like our comparator countries: a little bit ahead of countries like Germany, the United Kingdom and Australia and a little bit lower than countries like Belgium, Sweden and France.

Change in Canada’s GDP per capita ranking if non-permanent residents were held at 2% of population

Data Source: OECD Data Explorer. Quarterly GDP per capita growth, chained prices in USD

adjusted for PPP, Q1 2015 to Q3 2024. Includes OECD countries plus selected aggregates.

She also estimates that our GDP per capita will increase in the coming years simply due to planned reductions in temporary residents.

If this increase in GDP per capita comes to pass, it will of course not mean our economy is doing materially better or that Canadians will experience more economic well-being. This will be an artifact of how the measure is constructed. This research, and the conclusion, offers no commentary on the appropriate number of temporary residents Canada should accept, nor on the immigration levels plan itself. The estimates merely highlight that GDP per capita is not measuring what some seem to think it measures.

We don’t know if those who use GDP per capita as a hammer to complain about Canada’s poor economic performance understand the data and the metric. Do the individuals and organizations fixated on GDP per capita know that it will likely start moving in a positive direction soon, simply because we’re bringing in fewer temporary residents? And will it cease to be such a critical measurement for them when it does? Or will growth in GDP per capita be over-interpreted as a triumph of whatever economic policy they want to credit with the boost? We don’t know.

But we do know that it won’t mean our economy is any better, which is what some seem to imply every time they use the measure as a yardstick for our economic well-being.

To further the point, Ireland has in recent years become a powerhouse of GDP per capita. It’s done so by becoming an international tax haven—an economic strategy that is neither replicable nor desirable for Canada or our peers. Ireland’s GDP per capita numbers are so removed from the reality of its people’s lives that the Bank of Ireland relies on alternative measures like Gross National Income or GNI to conclude that their economy is not in fact number one in Europe, but much lower (ranked somewhere between 8th and 12th in the EU in 2020, they think).

There are real economic challenges for Canada, most of which are shared by our peers. And the economic problems unique to Canada stem from how terribly we’ve messed up our housing policies, the growing concentration of asset ownership and the affordability challenges that working Canadians face.

By all means, we should be tracking Canada’s performance and advocating for policies that contribute to a stronger economy. But there are strong rationales for why economists put so little stock into the GDP per capita of wealthy countries, so let’s be smarter about what we’re measuring. Metrics like economic well-being, standard of living, affordability and median wealth are much better at determining how well Canadians are doing economically.

As we explained in this video, on just about every measure that really matters, Canada is already way ahead.

Share with a friend

Related reading

Watch the video: Are foreign takeovers good for Canada’s economy?

We all want more investment in Canada's economy. But as SCP Chair Jon Shell explains in this video, when it comes to foreign investment in the Canadian economy, or FDI, we have to ask: is it investment that builds? Or investment that buys? Because these are two very different things.

Mark Carney’s Davos speech is a manifesto for the world’s middle powers

Mark Carney's recent speech at Davos matters because it treats this moment as a rupture, not a passing disruption. It’s in this rethink, write Matthew Mendelsohn and Jon Shell, that there is also relief: “From the fracture, we can build something better, stronger and more just,” Carney said. “This is the task of the middle powers.” The world's middle powers are not powerless, but we have been acting as if we are, living within the lie of mutual benefit with our outsized and increasingly erratic neighbour. Without the U.S., the world's middle-power democracies are rich, powerful and principled enough that we can unite to advance human well-being, prosperity and progress.

Four reasons our economy needs employee ownership now

Employee ownership offers a timely solution to some of Canada’s most pressing economic challenges, writes Deborah Aarts in Smith Business Insight. Evidence shows that when employees share ownership, businesses become more productive, innovative and resilient. Plus, beyond firm-level gains, employee ownership can help address the coming mass retirement of business owners, protect local economic sovereignty, boost national productivity and reduce wealth inequality. There is enough data about the brass-tacks benefits of employee ownership to sway even the most hardened skeptic.