By Sarah Doyle and Jon Shell

In last year’s budget remarks, former Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland celebrated the “significant accomplishment” that Canada’s per capita foreign direct investment (FDI) was the highest in the G7, “driving growth, increasing productivity and boosting innovation.” She is far from the only politician to frame total FDI as a positive indicator of economic health, but this masks a more complicated picture.

Total FDI does not actually tell us much about the state of the economy. One large deal can significantly affect total FDI inflows, which can vary dramatically from year to year (swings of 40% are normal). Each deal will depend on idiosyncratic, sector- or company-specific considerations that are often disconnected from underlying national economic trends. Moreover, not all FDI is created equal.

FDI is a jumble of different types of investments with vastly different impacts on the Canadian economy–some clearly positive, some negative and some a mix of both. The category that raises the most questions, and that is the focus of this piece, is that of cross-border mergers and acquisitions, or M&A.

Understanding these nuances is important. Because FDI is used as a shorthand measure of economic health, it is simply assumed that more FDI is good for economic growth, productivity and business investment. And that makes it difficult for politicians to reject FDI transactions that undermine the wellbeing of Canada’s economy and workers. The ability to distinguish between beneficial and harmful FDI is even more important now, in the context of a global trade war and threats to Canada’s economic sovereignty.

In this explainer, we aim to unpack FDI: what it is, when it is and isn’t beneficial and why understanding these nuances matters.

What is Foreign Direct Investment?

FDI occurs when an investor from one country owns at least 10% of an entity in another country. Statistics Canada breaks FDI down into three categories: M&A, reinvested earnings and “other flows.”

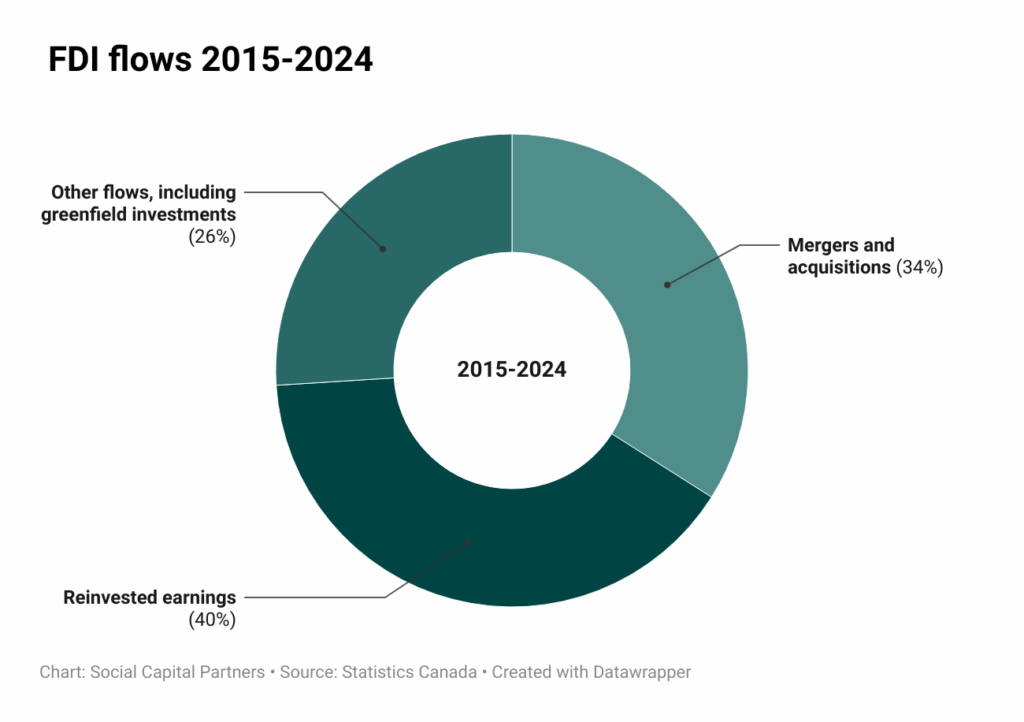

When we think of FDI, we typically imagine foreign capital enabling a new manufacturing plant to be built from the ground up. This is actually the rarest of the three main categories of FDI, often called “greenfield” investment. It’s included in the “other flows” category in Statistics Canada’s accounting, which on average has made up 26% of Canada’s inward FDI over the last 10 years (and includes a grab-bag of other transactions, like intracompany loans).

The biggest category of FDI inflow (40% between 2015-2024) is from foreign-owned companies keeping profits i Canada that could otherwise be sent to the owners as dividends. Whenever this money is kept in Canada, it’s called “reinvested earnings.” This might mean new capital investment, which could look a lot like greenfield FDI. But it also includes other things, like holding cash on the balance sheet to be sent out later as dividends. This category is included in FDI as an accounting convention but often isn’t very different from Canadian-owned companies retaining earnings for investment or other purposes. Because this category generally doesn’t give rise to contentious policy questions, we don’t dig deeply into it in this piece.

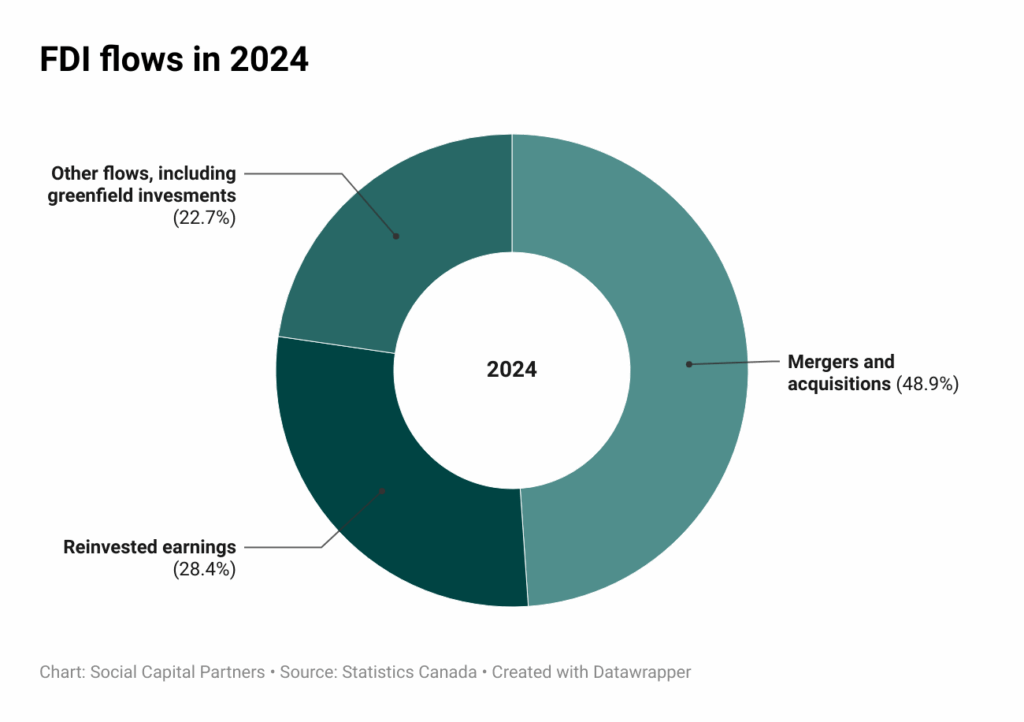

The final category is mergers and acquisitions, or M&A, where a foreign investor acquires at least 10% of a Canadian company. Over the last 10 years, this has accounted for 34% of all FDI (see Graph 1), and in 2024 accounted for almost half (see Graph 2).

Graph 1: Graph 2:

Graph 2:

The benefits of FDI

A typical definition of FDI will include a list of its many benefits to a country’s economy. In addition to supplementing domestic business investment (which is perennially lagging in Canada), FDI is said to create well-paid jobs, catalyze innovation spillovers and increase productivity from leading global companies bringing cutting-edge technology to Canada, connect local businesses to global supply chains and emerging markets and generate net-new economic activity and assets that contribute to GDP growth.

When describing these benefits, politicians, commentators and government agencies tend to focus on total FDI. Greenfield FDI does indeed hold the promise of delivering on these benefits, but they are far less likely in the case of cross-border acquisitions (M&A), which in many cases will have the opposite impact. Understanding these differences is critical to making informed policy decisions.

To unpack these differences, we’ll look at how greenfield and M&A FDI might deliver on the presumed benefits: investment capital, jobs, growth, innovation, productivity and access to new markets.

Greenfield FDI

Greenfield FDI is “where the magic of economic development really happens” according to the Financial Times fDi Intelligence team. The term “greenfield” is meant to describe the building of something new, where nothing previously existed – i.e. on a field that is currently green and empty. Canada’s experience with greenfield FDI includes many examples where investment capital has led directly to building new and useful assets.

Examples include the Travers Solar Project in Alberta, which produces about 465 megawatts of clean power and at peak construction employed around 800 people; Roquette’s investment in the world’s largest pea protein plant in Manitoba; Sanofi’s investment in a new vaccine manufacturing facility in Ontario and LNG Canada, a liquified natural gas export facility in British Columbia that was made possible through the largest private sector investment in Canadian history by a consortium of five multinational firms from different countries.

It’s clear how building a new asset can bring additional capital, create jobs and contribute to growth. The example of LNG Canada, which is enabling export to Asian markets, also demonstrates the potential of greenfield FDI to increase market access, while Roquette’s state-of-the-art pea protein plant is expected to reshore pea processing, shifting some processing from India and China to Canada. By using cutting-edge technologies, investments like these can also lead to innovation-driven productivity enhancements while enabling Canadian workers to develop transferable skills related to advanced technologies.

Greenfield FDI is not without its complexities. It is worth noting that, in a competitive global environment, governments often seek to attract greenfield FDI through some combination of subsidies and tax breaks. Public investment can be used to attract investment to projects that align with broader policy priorities beyond jobs and growth, like Canada’s net-zero goals. Increases in FDI inflows to Canada in recent years have been largely attributed to government subsidies focused on clean energy and electric vehicle value chains–although the latter, in particular, have attracted criticism, as have the significant subsidies that made LNG Canada possible. In other cases, incentives used to woo multinational tech companies to set up offices in Canada have been criticized for attracting talent away from Canadian-owned firms and facilitating the transfer of IP out of Canada. In the most problematic instances, tax breaks, in particular, can attract a version of greenfield FDI that does not yield the looked-for benefits (as has been true in Ireland). These deals can be tricky to get right. If they are well designed, however, their alignment with policy priorities can enhance their public value.

It is also possible that greenfield FDI could in some cases displace domestic firms or capital that could have achieved similar or even bigger impact with appropriate public support. This counterfactual is particularly important to consider in areas that are vital to Canada’s economic sovereignty. For example, Canada’s critical minerals strategy makes clear the intent to prioritize domestic ownership across the value chain, from exploration and extraction to downstream product manufacturing and recycling, in partnership with Indigenous communities, in order to maximize the economic, social and environmental benefits to Canada – a goal that would be undermined if new projects were built and owned by foreign capital.

However, while each instance will have different trade-offs requiring careful consideration, in general, where greenfield FDI creates a new asset that would otherwise not have been built with domestic capital, claims of new jobs, growth, increased productivity and innovation and expanded market access are likely justified.

M&A FDI

Foreign acquisitions of Canadian firms present a very different picture, as the capital involved pays for very different things, and that drives different outcomes for jobs, for growth, productivity and innovation, and for market access.

Capital investment

In a typical M&A FDI deal, capital is used to pay existing shareholders. Unlike in greenfield investments, the capital is not used to build new assets in Canada. We’ve found this to be the most common misconception when discussing this topic, and it’s a critical one.

A common rejoinder to proposals to restrict FDI is to ask where the capital will come from, if not from foreign sources. While this may be valid in the case of greenfield FDI, this argument doesn’t make sense when applied to M&A. If an acquisition doesn’t happen, in most cases no replacement capital is required as the target Canadian company will simply continue to operate under Canadian ownership.

Further, the availability of investment capital will often be reduced by M&A FDI for two reasons. First, acquisitions are often funded with debt that will sit on the balance sheet of the acquired company, which may crowd out investment capital. For example, in the case of Parkland’s recent decision to sell to U.S.-based Sunoco, new debt of $2.65B USD will provide the capital required to pay shareholders. Second, the acquirer will often have operations in multiple countries, driving competition between jurisdictions to fund new projects.

Jobs

Acquisitions, foreign or domestic, are often predicated on “synergies” where jobs (usually high-paid head office, R&D or manufacturing jobs) are made redundant in the combined company as capacity is optimized and departments and functions are merged. These savings are how the acquiring company justifies paying a price high enough to get a deal done and will often occur at the acquired company.

This dynamic has been evident in Canada. AMD’s acquisition of ATI, the China National Offshore Oil Corporation’s (CNOOC) purchase of Nexen and U.S. Steel’s acquisition of Stelco all led to layoffs, the last of which resulted in a government lawsuit. The most recent example is the closure of Crown Royal’s blending and bottling facility in Amherstburg, Ontario, with those jobs moving to the U.S., causing Premier Doug Ford to pour out a bottle at a press conference as he lashed out at British owner Diageo. While each instance has its own context and explanations, these outcomes are not surprising as they are a common and often intentional outcome of M&A transactions.

Growth, productivity and innovation

Two of the most commonly cited advantages of FDI have to do with the expertise of multinational firms: increased productivity and transfer of the latest technology to the host country. But a recent German study looking at 25 years of German M&A FDI found no evidence of increased output (i.e. no growth) and revealed that almost all productivity gains were a result of reduced employment. It concluded that while technology transfer may be important in acquisitions in a less developed economy, it was not evident in Germany’s advanced economy. In economies where R&D and knowledge workers are more prevalent, like Canada, FDI may be more likely to seek to acquire new technologies and talent than to bring them to the country.

In statements about FDI’s productivity-enhancing benefits, the research cited rarely focuses on acquisitions, instead pointing to studies that find foreign-owned firms to be more productive than domestic ones, and implying that all FDI shares equally in this benefit. (In this Fraser Institute article, for example, only one of the studies cited to support these claims focuses on acquisitions, and the findings of this study are likely explained by the job losses described in the more recent German study). It is reasonable to assume that a greenfield investment in a new factory will use the latest technology and perhaps add competition to the market. While an acquisition could, in some cases, result in the foreign buyer upgrading facilities with cutting-edge technologies, this is unlikely to be a common occurrence and should not be assumed to be a benefit.

Canada’s experience is almost certainly similar to Germany’s. There are many examples of outward technology transfer. AMD’s acquisition of ATI was to acquire ATI’s technology, not to improve it. CNOOC’s acquisition of Nexen in 2013 was explicitly to transfer Nexen technical know-how to China. Alphabet recently acquired North and AdHawk in order to gain technology they didn’t previously have.

These acquisitions all represent the sale of Canadian technology and knowledge to other countries. They are detracting from, rather than contributing to, Canada’s innovation ecosystem and potential for future innovation-driven productivity and growth.

Access to markets

There is likely some validity to the claim that cross-border acquisitions can provide greater access to export markets for the acquired Canadian company. This could occur in cases where the acquiring company is well established in foreign markets and the acquired company is not, but produces a readily exportable product that is complementary to the acquiring company’s existing product line. In an ideal scenario, this could lead to an expansion of operations in Canada to service foreign market demand. This ideal scenario most definitely does not apply in all cases, however.

The winners in M&A FDI

Acquisitions, both foreign and domestic, have a long and well documented history of disappointing outcomes. But they are not without their winners. Aside from selling shareholders who are presumably getting a good price, senior executives at both firms stand to gain bonuses if they stay and golden parachutes if they leave. Executive pay also increases when companies get bigger through acquisition. Transactions are also very lucrative for the investment bankers and lawyers who manage the transaction and the accountants and consultants who help with integration.

To summarize, M&A FDI deals will benefit a relatively small number of people, whatever the outcome for the companies, workers and countries involved, but in most cases will not bring new investment capital into Canada, will often reduce Canadian employment, are unlikely to drive innovation-based productivity or growth and are often used to acquire Canadian technology, resources and expertise. There will be times when an acquisition will provide a benefit to Canada–for example, if the acquirer commits to a specific, near-term capital investment that was not already in the company’s plans or can improve access to global markets–but these are not typical.

Unless the acquiring company can prove otherwise, the base case for M&A FDI should be that it will not provide the benefits normally linked to FDI in commentary and textbooks.

The special case of technology start-ups

While M&A FDI deals involving Canadian tech start-ups typically fall well below the ICA thresholds for net benefit review by the government, it is worth noting that in these deals, the implications of preventing foreign acquisitions are harder to discern. On the one hand, tech startup founders and politicians have been complaining for years about how little advantage Canada gains from the IP it develops, with most of the benefit going to foreign companies through licensing deals and acquisitions (i.e. M&A FDI). On the other hand, funding for tech start-ups is very different from that of traditional businesses as these companies rarely generate cash or pay dividends, and access to venture capital often depends on the promise of a lucrative “exit,” when the company either lists on a public market or, far more likely, is acquired by a larger (often U.S.) competitor. There is a legitimate concern that if foreign companies were prevented from buying start-ups, access to venture capital in Canada would be far more constrained. We don’t have a clear answer to the question of how to balance these concerns, but others have written about how to facilitate paths to scale that don’t require foreign acquisition, and Ottawa is actively pursuing policies with this aim.

Why this matters now

When the Investment Canada Act (ICA) was enacted in 1985 by the Mulroney government, its objective was to encourage foreign investment, limiting reviews to larger transactions that could be “injurious to national security,” in place of the previous Foreign Investment Review Act (FIRA), which allowed for review of all FDI transactions and required a demonstration of significant benefit to Canada.

The ICA succeeded in ushering in an era of significant inward and outward investment, especially between the U.S. and Canada. While the Act has been strengthened several times, it has almost never been used to block acquisitions. However, forty years after its introduction, Canada faces a starkly different world, and the focus is shifting from encouraging investment to protecting Canadian economic sovereignty.

To that end, in March 2025, former Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry, François-Philippe Champagne, tightened ICA guidelines in response to direct threats from the U.S., the primary buyer of Canadian assets. It expanded its scope to protect against “the potential of the investment to undermine Canada’s economic security” in the face of “opportunistic or predatory investment behaviour by non-Canadians.”

There is no sign that the risks that drove the Minister to act are abating. The American administration is currently leaning on U.S.-owned companies to support its geopolitical objectives in relation to China. It would be naive to ignore the possibility that American owners of Canadian companies might be pressured to “undermine Canada’s economic security.” U.S. President Donald Trump has already signaled that he could use “economic force” to redraw the Canada-U.S. border or pursue annexation or simply to get the trade deal he wants. Just recently, Ontario’s Premier Doug Ford lashed out at the CEO of U.S.-based Cleveland-Cliffs, owner of Hamilton’s Stelco, for acting against the interests of their Canadian division and putting Canadian jobs at risk by pushing for higher American steel tariffs.

Canadian assets under U.S. ownership–for example, critical minerals mining operations, manufacturing plants and energy and electricity infrastructure–could be turned into bargaining chips, with implications for jobs, consumer prices, supply stability, domestic competition and future investment decisions.

In the face of these threats, FDI policy could be strengthened further, perhaps applying the standard set in 2024 for the critical minerals sector, where foreign investment is allowed only “in the most exceptional of circumstances,” to all M&A FDI. The threshold for net benefit review could also be lowered. Proponents of the rare acquisition deals that could be beneficial would still be able to make their case.

If more foreign acquisitions of Canadian companies are rejected, there will be some who argue this is a mistake, trotting out reasons Canada needs FDI that simply don’t apply to acquisitions. With Canada facing investment, employment and productivity challenges, the arguments to ignore geopolitical risks will be compelling. Understanding why these deals may in fact hinder investment, jobs and productivity will be critical in winning the argument in the public square.

One argument that will surely be used in favour of accepting foreign acquisitions is that actions Canada takes to reject deals could cause the rejected country to respond in kind. It is indeed likely that the U.S. – currently the main destination for outward FDI – would retaliate by restricting the ability of Canadian companies and investors, such as pension funds, to make investments in America. Economic sovereignty isn’t free, and this is a price we should arguably be willing to pay. Simply put, a dollar of investment by the U.S. into Canada yields a lot more control than a dollar of investment by Canada into the U.S. For example, while Sunoco’s purchase of Parkland would represent 15% of Canadian gas stations, a similar purchase by a Canadian company in the U.S. would represent less than 2% of those in America. While there might be some small sacrifice in returns for Canadian investors, in the current geopolitical environment, shifting investment to other countries or ideally to investing at home is a rational strategy.

Getting comfortable saying “no”

Many reports have been written about the pros and cons of FDI inflows in Canada. Despite that, both the fact that it is actually a poor barometer of economic health and the clear difference between greenfield and M&A FDI remain broadly misunderstood. Our objective here is to create a basic understanding of what FDI is and of when it is likely to be beneficial or harmful, and to provide language to those seeking to protect against cross-border acquisitions that could undermine Canada’s interests.

We know that FDI deals provide conflicting incentives for politicians. Rejecting transactions that are not in Canada’s best interest also reduces the total value of FDI. As long as FDI is seen as a barometer of economic health, politicians will be under pressure to ensure this number goes up, and to ignore the very different implications of different forms of FDI. But current threats to Canada’s economic sovereignty should override this tendency and we should expect to see some deals rejected. Ideally, this will lead to a shift in how FDI is described and analyzed, introducing long-absent nuance and sophistication to the public discourse and making it easier for politicians to analyze each new transaction on its merits.

This would be a good thing. For forty years, Canada’s default approach was to be “open for business,” which often led to the sale of important Canadian companies and assets, costing jobs and innovation capacity. Becoming comfortable saying “no” in the face of opposition from influential vested interests, and getting better at explaining the downside of acquisition FDI, will help both in the face of immediate geopolitical risk and in Canada’s long-term effort to build a more resilient economy.

Share with a friend

Related reading

A youth employment supplement could rebalance Canada’s generational divide | Policy Options

Canada is overdue for a broader debate on intergenerational fairness and how our taxes and benefits support—and exclude—different age groups. As Kiran Gill and Matthew Mendelsohn explain in Policy Options, we continue to live with programs designed by baby boomers to provide security to seniors, even if those seniors are well off. Meanwhile, young adults in our country face challenges entering the labour market, securing stable employment and saving to build some measure of economic security in the face of rising costs. They propose a policy designed to make the economy work for younger Canadians—a youth supplement to the existing Canada Workers Benefit. This youth employment supplement—aptly coined a YES!—could help rebuild financial security and allow younger adults to buy homes, finance education for themselves or their children and save for the future.

Sign the open letter | Make the Employee Ownership Trust incentive permanent

Employee Ownership Trusts (EOTs) offer a practical succession pathway that keeps businesses Canadian-owned, empowers employees to share in the value they help create and supports long-term investment in our communities. With the right policy support, employee ownership can be a strong, proven path forward for Canada’s economy. If this is something you support too, you are invited to read and sign Employee Ownership Canada’s national open letter.

Watch the video: Are foreign takeovers good for Canada’s economy?

We all want more investment in Canada's economy. But as SCP Chair Jon Shell explains in this video, when it comes to foreign investment in the Canadian economy, or FDI, we have to ask: is it investment that builds? Or investment that buys? Because these are two very different things.