From Guidelines to Action: Feedback on the Proposed Merger Enforcement Guidelines

Background

Social Capital Partners (SCP) is a nonprofit that uses our private-sector experience and public-policy expertise to develop practical policy ideas that help working people build wealth, ownership and economic security.

As we’ve witnessed the increasing consolidation of corporate power in Canada in recent decades, we have concluded that it is impossible to achieve our aims of a fairer, more dynamic, more broadly owned economy without strong competition.

This thinking informed our 2023 submission to the consultation on the review of the Competition Act and our 2025 submission to the consultation on updated Merger Enforcement Guidelines.

Our most recent submission focused on serial acquisitions and the negative impact they can have on our economy. In the time since that submission, serial acquisitions have continued unabated.

For example:

| Pharmacies | In 2025, Neighbourly Pharmacy Inc. announced the acquisition of 33 additional pharmacies across Canada. |

| Primary care clinics | WELL Health acquired 13 primary care clinics in 2024, followed by an additional 9 in 2025, with 34 acquisition opportunities in the pipeline. |

| HVAC | Starting in April 2025, U.S.-based AIR Control Concepts has acquired four HVAC providers, O’Dell HVAC Group, Longhill Energy Products, Airsys Engineering and Rae Mac Agencies. |

We can’t say for sure that any of these particular deals will have negative impacts on their customers or communities, but at a time when Canadians are anxious about making ends meet, the evidence shows they come with real risks to both quality and affordability.

Research from the United States has found that consolidation in healthcare services often leads to worse quality of care, while prices for consumers don’t improve—and sometimes even rise. Similar research on the heating and cooling industry shows that, in markets where HVAC competition quietly erodes, prices increase.

Economic sovereignty is not just about control over essential physical infrastructure, like ports and telecoms. We allow our sovereignty to be chipped away when critical sectors like healthcare, housing repairs and childcare become consolidated in fewer hands – often foreign hands – in ways that make local markets less competitive and create undue obstacles for entrepreneurs to come in and start a business. When private equity (PE) firms systematically consolidate these sectors through serial acquisitions, they gain leverage over critical services, extract wealth and create higher barriers for Canadian entrepreneurs.

In an era in which the U.S. government is using its own companies to advance aggressive foreign policy objectives and openly discussing economic coercion against Canada, allowing further concentration of market power is a strategic vulnerability we cannot afford.

Summary of our feedback on the proposed Merger Enforcement Guidelines

We appreciate the opportunity to provide feedback and believe that the proposed guidelines meaningfully strengthen the clarity and credibility of merger enforcement in ways that are consistent with SCP’s concerns regarding (i) serial acquisitions, (ii) safe harbours and (iii) labour market impacts.

i. Serial acquisitions

SCP recommended that the Bureau more explicitly address serial acquisitions. We are encouraged to see that the Proposed Guidelines clearly articulate the right to examine all or part of a series of acquisitions as a merger, “even if each is not individually notifiable.” We are also pleased to see the proposed guidelines explicitly acknowledge the risks inherent from serial acquisition, by stating “where a firm engages in a series of acquisitions in the same market, each subsequent acquisition may be more likely to result in a substantial lessening or prevention of competition.” This is directionally aligned with SCP’s objective of ensuring that incremental consolidations are

properly assessed in a manner that recognizes their cumulative harm.

ii. Safe harbours

SCP recommended removing or avoiding “safe harbour” framing that could be interpreted as discouraging scrutiny of mergers below certain market share thresholds and are encouraged that the proposed guidelines have moved away from safe-harbour-style signaling.

iii. Labour market impacts

SCP recommended highlighting how labour market impacts should be considered in merger analysis and strongly welcomes the clear inclusion of labour market considerations in the proposed guidelines. This addition appropriately reflects a growing body of policy attention to labour market power as a dimension of competition.

Operationalizing the guidelines

While formalizing the proposed guidelines would be an important step, the real test will be in how the guidelines are operationalized.

We know that the final Merger Enforcement Guidelines will not be a document that is meant to contain details related to operationalization, but we hope that the Bureau will actively and publicly pair their enforcement power with the targeted operational recommendations we outlined in our 2025 submission. Specifically, we recommend that the Bureau:

Identify and more closely track PE firms operating in Canada

Given the outsized role that private equity (PE) firms play in leading anti-competitive efforts to consolidate markets through below threshold acquisitions, the Bureau should allocate dedicated resources to identifying and following the activities of the leading PE firms operating in Canada. This may involve engagement with expert stakeholders, monitoring key data sources, partnering with local governments to monitor mergers regionally, continuing to advocate for the development of a Beneficial Ownership Registry to increase transparency around consolidation patterns and/or introducing legislative tools that compel closed-end funds to report on any acquisitions within Canada.

Issue an open call on the impact of serial acquisitions on consumers and local economic resilience

Seeking feedback from across the country on the impact of roll-ups is an opportunity to access critical information on patterns of transactions that are often opaque and impact a diffuse cross-section of customers. The open call would ideally be done in partnership with local governments and could be specific to sectors like healthcare or be targeted more broadly. Similar efforts are being undertaken in other jurisdictions, with the White House tasking the DOJ, the FTC and the Department of Health and Human Services with issuing a joint Request for Information seeking input on the increasing power and control of the healthcare sector by PE firms. Given the interconnectivity of trade and economic power across the United States and Canada, it would be strategic to follow the United States’ lead and conduct parallel research to inform potential joint action.

Leverage market study powers to obtain information on non-reportable mergers in sectors ripe for serial acquisition

Given the opacity of serial acquisition patterns, the Bureau should take a proactive role in undertaking market studies to understand the state of sectors that are particularly vulnerable to serial acquisition. We suggest a particular emphasis on sectors in the care economy (e.g. long-term care homes, daycares, pharmacies etc.) as these markets are showing clear signs of distress and play a critical role in the health and functioning of our society.

Communicating the guidelines

We also believe that maximizing the effectiveness of the proposed guidelines requires increasing the accessibility of merger information. Canadians are more interested than ever in competition and the impact it has on our economic strength and resiliency. This energy should be leveraged and capitalized on by ensuring that access to pertinent information is available. Specifically, we recommend that the Competition Bureau:

Update the Report of Merger Reviews to be more accessible

SCP welcomes recent changes to the Report of merger reviews, including weekly updates and the inclusion of ongoing reviews. However, examples from jurisdictions like Australia and the European Union, offer valuable models for providing additional information that could improve public transparency regarding merger activity. Specifically, we recommend that the Bureau update the database to include:

- Plain-language summaries of the proposed mergers

- Plain-language summaries of merger decisions

- Relevant decision documentation (not including any sensitive information)

- Links to any additional merger reviews that either party has been involved in

- An option to be notified of new merger reviews as they are announced

Prioritize plain and accessible language in guidance and public information.

Canadians increasingly recognize the importance of competition policy to how people experience the economy. This growing awareness calls for a commitment from the Bureau to ensure that both its guidelines and public information are as accessible as possible. It’s no longer just lawyers and consultants delving into this content, but working Canadians who are concerned with the impact of mergers and acquisitions on their wages, consumer choices and economic well-being. SCP recommends that the Bureau make a concerted effort to prioritize clear, plain-language communication, including providing concrete examples to help Canadians understand the real impacts of economic activities.

Conclusion

The proposed guidelines represent meaningful progress in preserving and protecting competition in Canada. We strongly support their formalization.

However, we believe that the operationalization of these guidelines will be the real test of their impact. Guidance documents shape expectations, but enforcement outcomes shape behaviour. Serial acquirers are sophisticated actors who model regulatory risk into their strategies. If the Bureau does not demonstrate visible capacity to track, analyze and challenge roll-up patterns, market participants will correctly interpret updated guidelines as symbolic rather than substantive.

At a moment when Canada faces unprecedented economic pressure from the United States, allowing continued consolidation of key sectors through unchallenged serial acquisitions weakens our economic resilience and strategic autonomy. The Bureau has the mandate and the opportunity to act.

A youth employment supplement could rebalance Canada’s generational divide | Policy Options

By Kiran Gill and Matthew Mendelsohn | This post originally appeared in Policy Options

The Canadian economy is leaving many young people behind. Young adults today face unemployment rates reminiscent of a recession as well as a housing crisis that leaves many unable to afford necessities. Some 78 per cent of Canadians expect the next generation to be worse off than their parents. Growing wealth inequality has made young people even more pessimistic as they see mounting evidence that the economy is not working for them. They are earning less, saving less and face high barriers to owning assets unless they have help from family.

We also know that Canada’s taxes and benefits are skewed heavily towards serving older people. It is estimated that government spending on those 65-plus is three to four times greater than on those under 45. While Old Age Security (OAS) has become more generous over the last 50 years, government transfers to younger Canadians remain unchanged. At the same time, many seniors pay little or no tax thanks to overly generous tax exclusions, deductions and credits.

Last fall’s budget extended small amounts of funding to various youth employment programs, but the overall numbers don’t lie. The budget includes an increase of $28.3 billion in OAS spending by 2029, but less than $1 billion in new youth employment spending. As our policymakers grapple with how to structure a broad policy response to changes in global economics and geopolitics, we need to address problems with our taxes and benefits as well.

A youth employment supplement (YES) to the Canada Workers Benefit (CWB) would be a creative, scalable, cost-efficient way to motivate young people to get a job, as well as help those who are working but don’t make enough to save and invest. An early version of this model was proposed in a project by graduates Gabriel Blanc, Samuel De Grâce, Kiran Gill and Jacob Kates Rose from the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University.

The Canada Workers Benefit

The CWB offers means-tested tax relief to lower-income working Canadians in the form of a refundable tax credit. All Canadians over 19, except those who are enrolled in post-secondary education or are incarcerated, become eligible for the benefit after the first $3,000 of employment income.

The refundable tax credit increases as income goes up. In 2025, it topped out at $1,633 for individuals and $2,813 for families. The CWB is gradually reduced once adjusted net income reaches a certain threshold. No benefit is received if net earnings are greater than $37,742 for individuals and $49,393 for families. Alberta, Quebec and Nunavut have different negotiated thresholds. Federal legislation allows provinces autonomy in how the CWB is structured.

The CWB, which grew out of a similar benefit introduced in 2007, has had support across the political spectrum and has encouraged people to work and helped reduce poverty (page 29) amongst those who are employed. However, young people are the group most likely to live in poverty and the workers benefit does not do enough for them.

How would a youth employment supplement work?

A youth employment supplement could be created through an amendment to the Income Tax Act that would double CWB payments for single workers between 19 and 29 years old to an additional maximum of $2,000. To ensure the YES were properly targeted, the supplement would be calculated using existing CWB phase-in and clawback rates. Based on 2024 tax data, the average YES benefit for singles would amount to $1,179.

The supplement would not place any administrative burden on recipients. The Canada Revenue Agency would be able to determine eligibility and disburse funds using existing tax data. Based on the current proportion of CWB recipients between the ages of 19 and 29, a YES could benefit close to two million Canadians. And, as the CRA expands automatic filing, even more young workers could seamlessly receive the benefit.

Expected impact

Young adults today face higher hurdles to economic security, home ownership and saving for retirement or emergencies than previous generations. And building assets requires disposable income to invest and save. A 2024 report from Statistics Canada found that 55 per cent of people between the ages of 25 and 44 had difficulty meeting day-to-day expenses. . And a rental survey last summer found that almost half of respondents between 18 and 24 were spending more than 50 per cent of their income on rent, while facing an increasingly insecure job market.

At the same time, young people are carrying growing debt that many are unable to pay off. These debts are increasingly to private credit services that charge extremely high interest rates. A YES would not only help young Canadians meet basic needs, but would also aid them in establishing a viable financial foundation.

Income support programs like this have been shown to improve post-secondary educational outcomes and workforce participation. Research also shows that programs like a YES encourage financial planning and help maintain a stable, consistent standard of living in the face of uncertain income patterns.

Canada is facing significant economic transformation driven by climate change, technology and a rupture in North American and global trading and security. Although the long-term trends are uncertain, we are already seeing reduced hiring, particularly for entry-level professional jobs. Our taxes and benefits need to provide more security and income support to younger workers.

Costing and potential funding sources

In the 2024 tax year, a YES for single adults, defined as those with no spouse or dependents, would cost $2.29 billion. This figure does not include the cost of any changes to the disability supplement (to the CWB) or a YES for couples. These would need to be designed differently and would have additional costs.

By encouraging young adults to work, the added supplement to the CWB would, over time, lead to workforce retention and increased employment rates. And due to its inherent flexibility, it could easily be scaled or altered. Additional income tax revenue from the YES would also offset some of the costs.

New targeted programs, such as a YES, could be funded by reforms to our taxes and benefits. Paul Kershaw, founder of and lead researcher at Generation Squeeze, estimates that modest changes to Old Age Security and age and pension income tax credits would save between $14 billion and $19 billion annually.

An agenda for young adults

Canada is overdue for a broader debate on intergenerational fairness and how our taxes and benefits support — and exclude —different age groups. We continue to live with programs designed by baby boomers to provide security to seniors — even if they are well off. Yet young adults in our country face challenges entering the labour market, securing stable employment and saving to build some measure of economic security in the face of rising costs in almost every sector.

There is almost no government agenda to address this growing disparity. We need policies designed to make the economy work for younger Canadians and to show that Ottawa is responding to their needs. A youth employment supplement could help rebuild financial security and allow younger adults to buy homes, finance education for themselves or their children and save for the future.

Editor’s note: The authors would like to acknowledge Jennifer Robson, Paul Kershaw and Gillian Petit for their insightful comments.

Sign the open letter | Make the Employee Ownership Trust incentive permanent

Employee Ownership Trusts: A Canada-strong solution

Make Employee Ownership Permanent

To the Honourable François-Philippe Champagne

Minister of Finance of Canada

Canada is at a pivotal moment. As thousands of business owners prepare to retire in the coming years, the decisions we make now will shape who owns Canada’s economy, where wealth is created, and whether communities across the country continue to thrive.

Employee Ownership Trusts (EOTs) offer a proven, community-oriented solution.

Employee Ownership Trusts are an answer to succession. They enable business owners to sell their companies to their employees, and be paid out of company profits over time. They keep businesses Canadian-owned, enable workers to share in the success they help create, and support long-term investment in local economies. They align directly with Canada’s goals of economic sovereignty, worker opportunity, and resilient communities.

Canada has already begun to see the promise of this approach. The country’s first Employee Ownership Trusts are strong, values-driven companies rooted in their communities and focused on long-term success. Financial institutions, advisors, researchers, and workers are beginning to build an ecosystem ready to support employee ownership at scale.

What the market needs now is certainty.

Making the Employee Ownership Trust capital gains tax incentive permanent would unlock broader adoption, support thoughtful business succession planning, and allow employee ownership to become a mainstream pathway.

This is an opportunity for Canada to:

- keep successful businesses in Canadian hands,

- empower workers to build lasting wealth and stability for their families, and

- strengthen productivity, investment, and growth in communities across the country.

Employee ownership has delivered strong results in peer economies such as the United States and the United Kingdom. With permanent policy support, it can do the same in Canada.

We urge the Government of Canada to act swiftly to make the Employee Ownership Trust incentive permanent and embed employee ownership as a durable pillar of Canada’s economic future. This is a practical, forward-looking step that benefits workers, businesses, and communities — and helps ensure a stronger, more resilient Canada.

Signed,

Canadians who believe in shared ownership, strong communities, and a Canada-strong economy

Watch the video: Are foreign takeovers good for Canada's economy?

We all want more investment in Canada’s economy. But as SCP Chair Jon Shell explains in this video, when it comes to foreign investment in the Canadian economy, or FDI, we have to ask: is it investment that builds? Or investment that buys? Because these are two very different things.

Mark Carney's Davos speech is a manifesto for the world's middle powers

By Matthew Mendelsohn and Jon Shell

Mark Carney’s recent speech at the World Economic Forum matters because it says plainly what too many leaders have avoided saying out loud: middle powers like Canada are not powerless, but we have been acting as if we are.

We have been “living within the lie” of mutual benefit with our outsized and increasingly erratic neighbour. But the good news is that discarding that façade makes it possible to remake our alliances in ways that could actually shore up our economy and better secure prosperity and well-being for Canadians.

“I submit to you all the same that other countries, in particular middle powers like Canada, aren’t powerless,” the prime minister said. “They have the power to build a new order that integrates our values, like respect for human rights, sustainable development, solidarity, sovereignty and the territorial integrity of states.”

At Social Capital Partners, we welcome the clarity of this call for a new order. It aligns with a clear-eyed understanding of how fragile the current global order has become, how its benefits are unevenly distributed and how badly it serves those without leverage. The vision also aligns with our deepest hopes to live in a world of peace, equality and democracy.

We are under no illusions.

There are valid critiques of the speech. It did not clearly name the role that decades of unrestrained capital have played in making peoples’ lives worse, delivering us to this moment. It didn’t identify that the very promoters of that system were sitting in the room with him in Davos. And it did not fully acknowledge Canada’s own habit of talking tough while failing to follow through.

All of that is true.

It’s also true that Canadians have made a series of choices over many decades that have left us deeply exposed. We do not own our digital infrastructure. We haven’t sufficiently protected the Arctic. We didn’t maximize our natural resources and lack sovereign industrial and defence capacity. We understand that Canada must choose which battles we will fight.

Carney stopped short of calling out Donald Trump by name but was blunt and overt in his rejection of what he called the mere illusion of sovereignty.

“When we only negotiate bilaterally with a hegemon,” he said, “we negotiate from weakness. We accept what is offered. We compete with each other to be the most accommodating. This is not sovereignty. It is the performance of sovereignty while accepting subordination.”

Oof. This line should land hard in Canada, because it describes much of our recent experience. We invoke independence while structuring our economy, trade and infrastructure around dependence. We describe integration as mutual benefit even when it leaves us vulnerable to coercion.

The system worked—for some. For many others, it did not. Naming that truth is a prerequisite for rebuilding legitimacy and a better global system.

Crucially, the speech did not lapse into fatalism, and many around the world have even characterized it as a rallying cry. He explicitly rejected the idea that smaller states must submit to the logic of greater powers, arguing that middle powers have real power if they choose to exercise it together.

This is not a sentimental claim.

Taken together, some of the world’s middle-power democracies, which Jon has previously suggested could include Canada, Japan, South Korea, Australia, France, Germany, Italy, the U.K., Spain and the Netherlands, would amount to about the same GDP as the U.S., with about six hundred million wealthy residents with massive buying power. Taken together, we also have vast natural resources, enormous pools of capital, many of the world’s most innovative firms and significant military and industrial capacity. We are among the most attractive places on earth to live in and invest in.

This is not marginal power. It is simply unorganized power.

That is why Carney frames the choice so starkly: “In a world of great power rivalry, the countries in between have a choice: to compete with each other for favour or to combine to create a third path with impact.”

The offering of a new Middle Power Alliance is compelling: we all believe in democracy, equality and freedom. We believe in international trade and the dignity of all people. And together, these commitments produce human well-being, prosperity and progress.

Competing for favour leads to fragmentation and a race to the bottom. Coming together opens the possibility of something more durable—and a hopeful vision that people and democracies can build something better.

“Collective investments in resilience are cheaper than everyone building their own fortress,” Carney told the group at Davos. The real question is not whether middle powers must adapt, because of course we must, but whether we adapt defensively or ambitiously.

Ambition here would mean countries coming together in a new way to share the load and think big: joint digital infrastructure, coordinated industrial policy, common standards, collective security where geography demands it and new multilateral institutions in areas like climate, health and research. We have done things like this before, and successes like the International Space Station are proof that advanced democracies can build together when we choose to.

Trump has made it perfectly clear that tariff threats to Canada are the new baseline. There is no winning strategy in standing alone; there is only waiting to be pressured again.

Coercion works when countries are isolated and fails when pressure triggers collective response. Especially on the heels of Carney’s speech being called “the most important foreign policy speech in years” by the likes of the BBC and The New York Times, Canada has a role to play in building this alignment.

The form of this middle-power group can vary—maybe it’s those core 10 countries, maybe you’d add Mexico, Brazil and the Scandinavians; maybe it’s NATO minus the U.S. plus a few key others, like South Africa. The group will undoubtedly grow over time. The big shift is that the alliances among democratic nations must be built without U.S. leadership. And, must show that democracy delivers real benefits to its people, so that the group grows and emerging economies have real allies—not just threats to fall in line.

Carney’s speech matters because it treats this moment as a rupture, not a passing disruption. It’s in this rethink that there is also relief: “From the fracture, we can build something better, stronger and more just,” he said. “This is the task of the middle powers.”

Whether or not this becomes a turning point depends on what comes next.

If the speech is met with caution and retreat, it will fade. If it becomes a mandate to build institutions, alliances and capacity, it could mark the beginning of a genuine third path to security and shared prosperity—out of a world drifting toward coercion and into one shaped by cooperation.

For the first time in a long while, that path is visible. More hope is possible. More ambition is possible. We have the power; we just have to organize. So, middle powers, unite!

Four reasons our economy needs employee ownership now

By Deborah Aarts | Part of our Special Series: the Ownership Solution | This post first appeared in Smith Business Insight

When you think of employee ownership, what comes to mind?

You might dismiss it as a fringe pursuit. You might think of it as an admirable, if seemingly impractical, approach to doing business. You might see it as a gesture of benevolence—a nice thing to do.

But have you considered employee ownership as an answer to some of society’s stickiest issues?

If you’re unfamiliar with the model, here’s a quick primer: Employee ownership is an umbrella term to describe corporate structures that distribute proprietorship among some or all workers—not just those at the top. In Canada, it tends to take three forms: worker co-operatives (in which all workers share ownership and participate in management), employee share ownership plans (which allow employees to amass ownership stakes as an incentive or as part of their pay), and employee ownership trusts, or EOTs (a new-to-Canada succession structure that allows owners to transfer shares of a corporation to an employee-owned trust in exchange for tax incentives).

For individual businesses, the advantages of employee ownership can be varied and substantial: Employee-owned companies have been found to be more productive, innovative, resilient, profitable and faster-growing than those with concentrated ownership structures. By now, there is enough data about the brass-tacks benefits to catch the eye of even the most hardened skeptic. (There’s a famous observation among those in the employee ownership space that it’s likely the only economic idea supported by both Ronald Reagan and Bernie Sanders—albeit for very different reasons.)

But the potential advantages go far beyond the scope of individual companies. In fact, experts believe employee ownership can help tackle some of the most pernicious economic problems facing Canada right now.

Smith Business Insight contributor Deborah Aarts spoke to members of the new Employee Ownership Research Initiative (EORI)—which is housed within Smith’s Centre for Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Social Impact—to understand why employee ownership might be a model for today’s moment.

Problem #1: The “silver tsunami”

Here’s a tough truth about the Canadian economy: It’s built on a bedrock of small- to mid-sized private enterprises, and a lot of their owners are getting out of the game. A 2023 report by the Canadian Federation of Independent Business found that more than three-quarters of Canadian small business owners said they intend to exit before 2033—yet fewer than 10 per cent had a succession plan in place. With some $2 trillion of assets on the line, this so-called “silver tsunami” represents a significant economic problem.

“There’s a generation of retiring business owners with no one to buy their businesses,” explains Melissa Hoover, who is managing director of ownership culture at Apis & Heritage Capital Partners (an investment fund focused on transitioning businesses to employee ownership models), a senior fellow at the Institute for the Study of Employee Ownership and Profit Sharing at Rutgers, and a member of the EORI advisory board. “Many think their only options are to close, to sell to a competitor or to get acquired by private equity—if they are big enough to attract interest. But more and more are starting to recognize employee ownership is an option—and in this moment, a really good one.”

In particular, the Canadian EOT mechanism—which became law in 2024 under the federal Income Tax Act—offers an enticing alternative to selling out or shutting down, by creating a smooth runway for employees to buy out shares and providing fulsome tax incentives to the selling owner(s). “The EOT structure allows exiting owners to maximize the monetization of their life’s work,” explains Elspeth Murray, associate professor and CIBC Fellow in Entrepreneurship at Smith, academic director of the Smith Master of Management Innovation & Entrepreneurship program, and director of both Smith’s Centre for Entrepreneurship, Innovation & Social Impact and the new EORI. “Furthermore, by transitioning ownership to people already working in the organization, it addresses the legacy question: Very few business owners want to just cash out and leave everyone on their team to their own devices.”

Problem #2: Sovereignty threats

As anyone who has recently scrutinized a grocery label knows, economic sovereignty is occupying considerable brain space among Canadians in the current global geopolitical moment. And while employee ownership won’t ameliorate the impact of tariffs or trade wars, experts say it can play an important role in keeping the domestic economy strong and free.

Why? Because the aforementioned silver tsunami is creating what some have described as a “perfect storm” for foreign takeover by private equity firms or multinationals. Employee ownership creates a financially compelling incentive for businesses to stay put. “It’s one way to help keep ownership of businesses within Canada, in Canadian hands,” explains Murray.

There are real economic reasons to encourage this, says Simon Pek, an associate professor at the University of Victoria’s Gustavson School of Business, where he also serves as associate director of the Centre for Regenerative Futures, and an EORI fellow and board member. “Private businesses are often considered anchor institutions in their communities,” he explains. “They create local jobs, support local supply chains and play a material role in keeping communities intact.” Transferring ownership to employees allows those benefits to continue, Pek adds, while increasing the likelihood that the venture will carry on for the long haul: “If a business is going to be sold, it’s far preferable, from a sovereignty perspective, for it to go to people with strong ties to the community than to a foreign company that might not think twice about shutting things down in the future.”

Problem #3: Lagging productivity

Economists, policy-makers and business leaders alike have long bemoaned the persistently lagging productivity of Canada’s economy. Correcting that will require, in the words of McKinsey, “unprecedented pace and bold action” on a number of fronts—and experts believe employee ownership can help.

There’s a growing body of research that demonstrates when companies pair employee equity ownership programs with organizational cultures that encourage participation and agency, productivity improves. “When you align the interest of workers and the interests of employers it creates a powerful incentive for folks to be more productive,” says Pek. “You see workers come forward with more innovative ideas and process improvements because workers clearly stand to benefit.”

Writ large, this contributes to a more productive economy overall, Hoover adds. “Employee ownership proves–in a really practical, meat-and-potatoes way–that not only is a multi-stakeholder economy possible, but that it actually outperforms single-stakeholder capitalist models.”

Problem #4: Wealth inequality

Finally, there’s the matter of wealth inequality. In Canada, the income gap—that is, the difference in the share of disposable income between the wealthiest and poorest households in the country—reached a record high in 2025. “There’s little doubt that there’s a widening gap between the haves and the have nots, and that it’s crushing the middle class,” comments Murray. “I think employee ownership offers an opportunity to help close that gap.”

Hoover considers employee ownership a “market-based strategy for tackling inequality.” She elaborates: “If you want to build wealth in our current economy, you have a few options: owning a house, inheriting money, accumulating stocks and owning a business,” she says. “For a lot of people the latter stands out as the most possible, especially when it’s a shared ownership strategy. It gives people access to a productive asset that keeps generating wealth and building assets.”

This is more appealing to owners than you might expect, Hoover says. They see the same headlines about rising costs and growing debt as everyone else, and most would prefer to be part of the solution than the problem. “If you ask selling owners about their No. 1 concern, it’s usually taking care of the people who work for them,” she says. “Many owners are drawn to the idea of sharing the value that’s created with the people who created it,” especially when there are favourable tax reasons for them to do so.

Furthermore, when workers get ownership (or a path towards it) it sparks all sorts of offshoot economic benefits: They might be able to buy a house, or invest in their communities, or simply maintain stable employment. “It can help address a lot of the issues we all care about,” says Pek.

Pek, Hoover and Murray all acknowledge that employee ownership is not a magic wand. It takes considerable time and effort for owners to implement an ESOP or an EOT, and it can require extensive legal, accounting and operational support to get the details sorted. However, all agree that the work can have a clear—and rewarding—payoff. “When it’s done properly, employee ownership is not as risky as it may seem,” Pek says. “In fact, it can be very valuable—for businesses, yes, but also far beyond that.”

Advice to the public service: Five ways to confront monsters and chaos

Events are accelerating quickly in the United States and in our hemisphere. Canadian governments—and the public service—were not designed to confront what we are experiencing.

We are witnessing a rapid collapse of the rule of law in the United States and a dramatic repudiation by Trump of the world order that the U.S. built and that kept Canadians safe. An authoritarian, imperialist America is quite obviously a threat to Canada.

Trump and Vance may fail in their attempt at regime consolidation. Their agenda is unpopular and opposition is rising, but they are supported by powerful malignant forces who have control over digital platforms, the information ecosystem and the tools of violence.

We don’t know what the U.S. will look like in two years. We should not count on free and fair elections this year. But we do know some of the things that 2026 holds for Canada.

The Trump regime will threaten its former allies and undermine democracies through intimidation. It will deploy maximum pressure against our economy and will continue to extort our people and businesses.

It will support campaigns of disinformation, targeted in ways to encourage disunity and hate, enabled by American Big Tech.

A transnational network of authoritarian billionaires— with access to huge pools of capital and technology platforms— will accelerate their attempts to undermine successful nation-states like Canada who act as a check on their ambition to replace democratic governments.

Most Canadians have understood all of this for a while, but the invasion of Venezuela and the threats to Greenland—plus the language used to justify them—make clear what the U.S. has become.

The Canadian federal government knows all of this. Even if most of our leaders make tactical decisions to bite their tongues, no one doubts any longer what is happening.

The federal government and the public service were not designed to deal with this kind of threat. Political and bureaucratic leaders are trying to re-wire the system quickly, but systems can’t deliver what they were not designed for. Vertically organized ministries, with highly segregated legal authorities and responsibilities, are not equipped for strategic, coordinated agile decision-making.

We need rapid changes to confront this national emergency and security threat. Those changes include the instincts, assumptions and habits of public servants and political decision-makers, but also organizational changes—called “machinery of government” issues.

Ottawa is starting to head in this direction. There is a recognition that processes and systems created in the Before Times are methodical, but are too slow and disjointed to respond in a strategic and integrated way to the current emergency. For example, the government has taken the necessary steps to create new Crown agencies, like the Major Projects Office and the Defense Investment Agency, to clear administrative hurdles and execute on strategic projects more quickly.

Let’s start with five “machinery of government” changes that I think are needed to meet today’s threats. I know that some of these are already in the works.

If Canada had more runway, some of this work could result in the creation of new stand-alone ministries, but that seems unlikely to occur in the next few weeks. But the assignment of full-time Ministers, Deputy Ministers and staff should be possible, even if the ministers don’t have full authority over a statutory department. Soft coordination methods like inter-ministerial results tables or working groups can be useful, but they will not be sufficient in many cases unless they are stewarded very carefully at the most senior levels. Five priorities should be:

Building democratic resilience

Our government is not designed to withstand systemic, orchestrated attacks on the institutional foundations of democracy. That should be obvious, as we have watched the global forces of chaos and autocracy undermine the capacity for democratic government in the U.S. The authoritarian playbook is not a mystery and it will be deployed in 2026 within Canada.

If Americans who are committed to democracy and the rule of law could go back to 2010 or even 2020, they would do many things differently to make the democratic state more resilient to attacks from democracy’s enemies. We need a Minister, properly supported, whose full-time job is to prepare for all the ways that the transnational authoritarian movement will seek to undermine the Canadian democratic state, and to take action to make the authoritarian project less likely to succeed. Reinforcing the independence and transparency of elections so that the public would quickly dismiss false claims of election fraud and improving support for civic, local and independent journalism are two of many steps that should be undertaken.

Governing Big Tech platforms

In 2018, I began work within the federal government to develop governance to more strategically confront the threat that digital platforms represented to our economy, national security, democracy and children, and to build capacity within the federal public service to treat them as geopolitical actors. This entailed assembling expertise from across multiple departments, all of whom were engaged with Big Tech with different objectives and on different issues, but were overmatched by the capacity of the world’s largest companies.

Although the government chose to defer decisions at that time, the case for action has only gotten stronger. Our options today are more constrained than they were a decade ago, but we need to mobilize across the system to ensure our digital sovereignty and have at least some democratic control over Big Tech.

Coordinating national security

Those charged with protecting Canadian national security and sovereignty are scattered across multiple agencies and ministries. The Canadian Armed Forces, the RCMP, Global Affairs, Public Safety, Industry, Fisheries, Justice and multiple security and intelligence agencies across multiple ministries have never been properly coordinated. That is endemic and, until this year, did not represent an existential threat.

I know work is underway to apply a more integrated lens and decision-making process to a variety of issues including foreign investment review, defense procurement, monitoring hate and the work of the Coast Guard. But organizational cultures, legal responsibilities and program authorities do not align easily or change quickly. Re-working this governance, in real time, is an urgent national priority.

Supporting the community and charitable sector

The not-for-profit sector, broadly defined, has no home in government. Private-sector industries—from agriculture to fisheries to natural resources to manufacturing and auto—know where to go in government when they need support meeting a vital need. Charities, foundations, community organizations, co-ops and not-for-profits have no Minister thinking of them first and how they can be supported—and how they can help meet urgent national priorities that play out in community.

While there are scattered offices in ESDC, Industry and the CRA, these are not designed to meet the needs of civil society organizations. These organizations, working in community, are going to be vital to Canada’s resilience. If Canada is to thrive in the coming decade, we will need to mobilize all sectors and the government needs to engage with them as strategic partners.

Preserving national unity

The federal government should build secretariats within the Privy Council Office to prepare for the inevitable onslaught of disinformation and illegal foreign intervention in Canadian issues. These campaigns will be designed to exacerbate and invent regional grievances and animosities in the context of discussions about Alberta and Quebec secession.

There will be many American agents of chaos looking to disrupt Canadian democratic processes and our sovereignty this year. A peaceful, democratic Canada that respects human rights and the rule of law is an important counterpoint to the world’s most dangerous authoritarian regimes and the dissolution of Canada would be a huge victory for the forces of global authoritarianism.

—

But machinery changes alone will not be enough. We need to rewire our brains, not just our organizations.

There are many ideas and habits deeply embedded in the federal government that are not right for this moment. Bringing new people and perspectives into the government—including private-sector, not-for-profit, community, faith and labour leaders—can help. Some of the changes in our mental maps are already underway, but will need to be intensified. To succeed, we will need:

Transparency and engagement. While it will be necessary to keep many plans secret, the federal government and public service need to be more transparent and engage more directly with leaders and communities across the country who can help them co-create and co-deliver solutions.

Innovative state capacity. We need to discard the deeply embedded neoliberal assumptions that have governed policymaking for over three decades and learn how to deploy the state in a strategic ways, using all the tools of industrial strategy to deliver positive economic outcomes.

More talk of shared citizenship and sacrifice. Governments need to talk more about our responsibilities as citizens. Our governments will have to ask more of us – and ask those of us with privilege and economic security to make sacrifices. That includes being very frank about the threats we face and how a peaceful, law-abiding democratic Canada—despite all its flaw—is the best hope for ordinary Canadians to have a meaningful, secure, prosperous life. Fascist countries with secret police who shoot down their citizens in the street are not great places for ordinary working people to live and thrive.

—

These are some early thoughts on evolving federal governance and I welcome others. I know people within the federal government are contemplating how to organize themselves to confront this national emergency and a belligerent United States. This is a time like no other in our history, and those making decisions have not been trained for this unprecedented threat—because we haven’t experienced anything like this before.

If those entrusted with the enormous responsibility to navigate Canada through this crisis approach the moment with humility, a willingness to discard some of the things they thought they knew and recognize that they will need help from across Canadian society, we can get through this. There are signs that this is happening, and I’m cautiously optimistic that our governments can organize themselves in new ways to meet this moment of peril.

How to get single family homes out of the hands of investors | Toronto Star

By Matthew Mendelsohn , Mike Moffat and Jon Shell | This post was published in the Toronto Star

Canada needs more rental housing. But it also needs to get existing homes out of the hands of investors and back into the hands of families. The federal government can achieve both simultaneously by fulfilling one of its key campaign promises — with a twist.

Many Canadians are angry about the state of Canada’s housing market, with a recent Abacus poll finding that 56 per cent of Canadians say housing should be a top-3 priority for the federal government. Yet only 28 per cent believe the federal government is on track to meet their housing goals. Many potential homebuyers feel they cannot compete with investors, who have been increasing their share of the resale market.

The federal government is taking some steps to address Canada’s housing crisis. There are programs designed to build new supply, preserve existing affordable supply and reduce demand. But one potentially powerful approach is missing from this suite of programs: incentivizing investors to move their capital to more productive uses…

Budget was missing a Canadian ownership strategy

By Jon Shell | Part of our Special Series: the Ownership Solution | This post first appeared in The Hill Times

The day before the Canadian federal budget was introduced, a Canadian gold mining company called New Gold announced that it would be acquired by American-owned Coeur Mining. This comes only a couple months after the proposed acquisition of one of Canada’s largest miners, Teck Resources, by British-owned Anglo American.

While government approval is still required for these deals to proceed, Ottawa recently signed off on Sunoco’s acquisition of Parkland Corporation, owner of over of 15% of Canada’s gas stations and an important refinery in B.C. That deal provides little or no benefit to the Canadian economy, has already resulted in job losses and turns critical infrastructure over to an American company.

This was the first real test of the newly beefed-up Investment Canada Act, which allows the government to reject acquisitions of companies like Parkland on economic security grounds. The test did not go well.

There was a time when deals like this could be dismissed as just the cut and thrust of global finance in an ever more connected world.

But the federal budget goes to great pains to explain that that those days are over and calls, many times, for “generational investments.”

You know what’s easier than making a generational investment? Not selling the things you already have.

As governments turn protectionist around the world, if Canada stays “open for business,” there’s a significant risk of a repeat of 2006-2007, when foreign investors scooped up major Canadian companies like Inco, Falconbridge, Noranda, Stelco and ATI.

The impact of the loss of head offices, research jobs and control over Canadian resources is still being felt today.

Recently, the current American owner of Stelco, one of Hamilton, Ontario’s major employers, came out in favour of the American tariffs on steel that are harming his own Canadian employees, raising the ire of Ontario Premier Doug Ford.

While the recent budget used the word “sovereign” 81 times, it did not define a clear strategy to build and maintain Canadian ownership of our assets.

When combined with its focus on attracting private capital, there’s a real danger that the federal government will enable a sell-off of Canadian companies to foreign investors. It’s even possible that this sell-off would be considered a “win” for the strategy, as it could be characterized as an investment in Canada.

This would be a mistake.

There is a significant difference between investing in building and investing in buying.

Building leads to new assets, like the Kitimat LNG terminal in B.C., funded in large part by foreign capital. Buying often leads to a loss of head office jobs, innovation capacity and sovereignty.

With the government signaling a willingness to sell Canada’s airports and ports in this budget, bringing back memories of Ontario’s disastrous sale of Highway 407 to a Spanish company, it’s dangerous to proceed without clearly defining what kind of foreign investment we’d accept.

The mistake could easily be corrected with four concrete steps:

First, the budget sets out to “build, protect and empower Canada.” A Canadian ownership strategy fits cleanly in the “protect” column. It could define Canadian ownership more narrowly and ensure that programs like the Scientific Research and Experimental Development tax incentive do not benefit foreign-owned companies.

Secondly, it could reject the proposed acquisitions of Canadian mining companies, making it clear Canadian ownership is a priority.

Thirdly, it could prioritize ownership structures that enhance sovereignty, like employee and community ownership.

Finally, it could tie all these together with other pro-Canadian measures in the budget, like the Critical Minerals Sovereign Fund into a strong and important narrative that Canadians would support.

When a Canadian company is sold, it can be decades before the impact is fully understood.

At the time of its sale to AMD in 2006, ATI, based in Mississauga, shared the global market for graphics chips equally with U.S.-based Nvidia. Today, Nvidia is the leading global supplier of chips that power AI, employes 36,000 people and is worth $5 trillion USD.

AMD bought ATI for $5.4 billion USD and employs fewer Canadians today than in 2006, despite promising to keep a major research centre in Canada.

The U.S. is leveraging Nvidia’s success in their trade war with China. Imagine if that power resided in Canada instead?

If we really want to build a Canada that is “confident, secure and resilient,” we can’t afford to repeat the mistakes of the past.

Sovereignty requires ownership. It’s clear that China and Trump’s America understand that. It’s time for the Canadian government to prove that Canada understands it too.

What the new World Inequality Report tells us, and why it matters for Canada

Economic growth is often treated as a shorthand for progress. As the old story goes, if our Gross Domestic Product (GDP) goes up, then we’re all better off.

But the latest World Inequality Report offers another sobering reminder that who benefits from economic growth matters just as much as how much the economy has grown. And the economic order keeps tilting further and further towards serving a tiny, ultra-wealthy minority.

This is why the World Inequality Database (WID) and this flagship 2026 report matter so much. Launched in 2018, the global effort brings together more than 200 researchers to track income and wealth inequality over time, building a shared global infrastructure to understand—and sometimes even expose—trends that were previously hidden or fragmented.

Canada is a part of this global network of experts, which is vital—because, as we have said in our own 2024 Billionaire Blindspot report, you can’t fix what you can’t see.

The most important new finding is that today’s inequality story is not primarily about the richest 10%, or even the richest 1%. It’s about what’s happening at the very top of the wealth distribution.

Globally, the richest 0.001%—think of them as roughly 60,000 people, or the world’s billionaires, or how many people can fit in a football stadium—have dramatically increased their share of total wealth.

In 1995, this group held about 3.8% of global wealth, but by 2025, that share had climbed to 6.1%. Over the same period, their personal wealth also grew at annual rates between 2% and 8.5%, far outpacing the bottom half of the population, whose wealth grew at just 2% to 4% per year.

When policy debates focus on “the rich” as a broad category, they miss the fact that most of the action is concentrated among a very small number of families (and tech bros) at the extreme top. Looking only at the top 10% or top 1% risks obscuring the true scale—and drivers—of wealth concentration.

Why does this matter? The evidence is overwhelming that growth that produces extreme inequality leads to less resilient, less healthy and less prosperous societies. And economic inequality drives prices and asset values out of reach, depriving ordinary working people from access to goods and services.

It also entrenches power.

“The result is a world in which a tiny minority commands unprecedented financial power, while billions remain excluded from even basic economic stability,” the authors, led by Ricardo Gómez-Carrera of the Paris School of Economics, write.

In Canada, too, although Canada’s GDP keeps going up, wealth gains have been concentrated at the very top. Many Canadian households are struggling to afford food and housing.

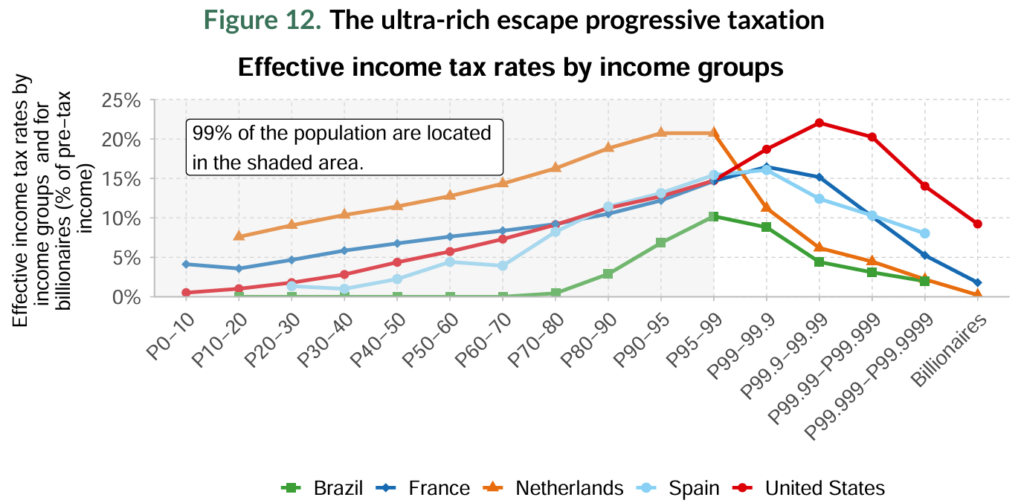

As our colleagues at the Canadian Tax Observatory have also pointed out, one key factor is taxation—or more precisely, who governments are willing or able to tax. International data in the report show a striking pattern: at the very highest income levels, effective tax rates actually decline (see Figure 12 from the report, below). In other words, the ultra-rich often pay lower effective tax rates than those who are merely “rich,” and in some cases, even lower than middle-income earners.

Canada-specific data at this level are notoriously hard to come by, but SCP’s own research suggests a similar dynamic. The wealthiest Canadians increasingly derive their income from capital gains, rather than wages, which are taxed at a lower rate. Our tax system, while containing many progressive elements, actually exacerbates the problem of growing wealth inequality. Because of tax breaks for capital gains and dividends, tax rates on income derived from wealth are lower than those on income derived from working. And that’s before even considering the kinds of sophisticated tax-planning and wealth sheltering strategies that only the wealthy tend to have access to.

The report ranks countries based on the number of data sources they use to measure wealth inequality and Canada sits in the middle of the pack—behind the U.S. and much of Western Europe in terms of transparency and data coverage.

Without high-quality data, policymakers are left debating inequality in the dark. The one-page country profiles in the World Inequality Report are short, but the Canadian profile is revealing. The report’s estimates show greater wealth concentration than the most recent Canadian Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) figures based on “rich lists.” For example, the report estimates that the top 1% in Canada hold about 29.3% of total wealth, compared to 23.8% in the PBO’s analysis.

Momentum is building in Canada for better wealth data. Statistics Canada recently released its first serious attempt at improving measurement of wealth at the top—something SCP has long called for. It’s a promising step toward shedding light on Canada’s billionaire blindspot.

The deeper challenge is policy. As Canada faces an unprecedented economic assault from the south, there is a risk that the policy instruments we deploy to encourage growth will exacerbate inequality. We do not want to encourage growth that sees all the returns go to those who already have extreme wealth. We need to tackle the structural dysfunction within the economy today that sees gains and redistribution flow almost entirely upward.

That means better ways for families and communities to build assets—like affordable housing, business ownership, retirement security and emergency savings—alongside tax and regulatory reforms that ensure fair taxation of the ultra-wealthy.

The World Inequality Report is clear: wealth inequality is not inevitable. It is the result of choices.

And when the richest 10% of the world’s population owns 75% of wealth and the bottom half just 2%, it’s time we choose something different.